Over the years, researchers from the Institute have scoured the mountains, deserts and ravines of South Africa and neighbouring countries seeking out and analysing rock art.

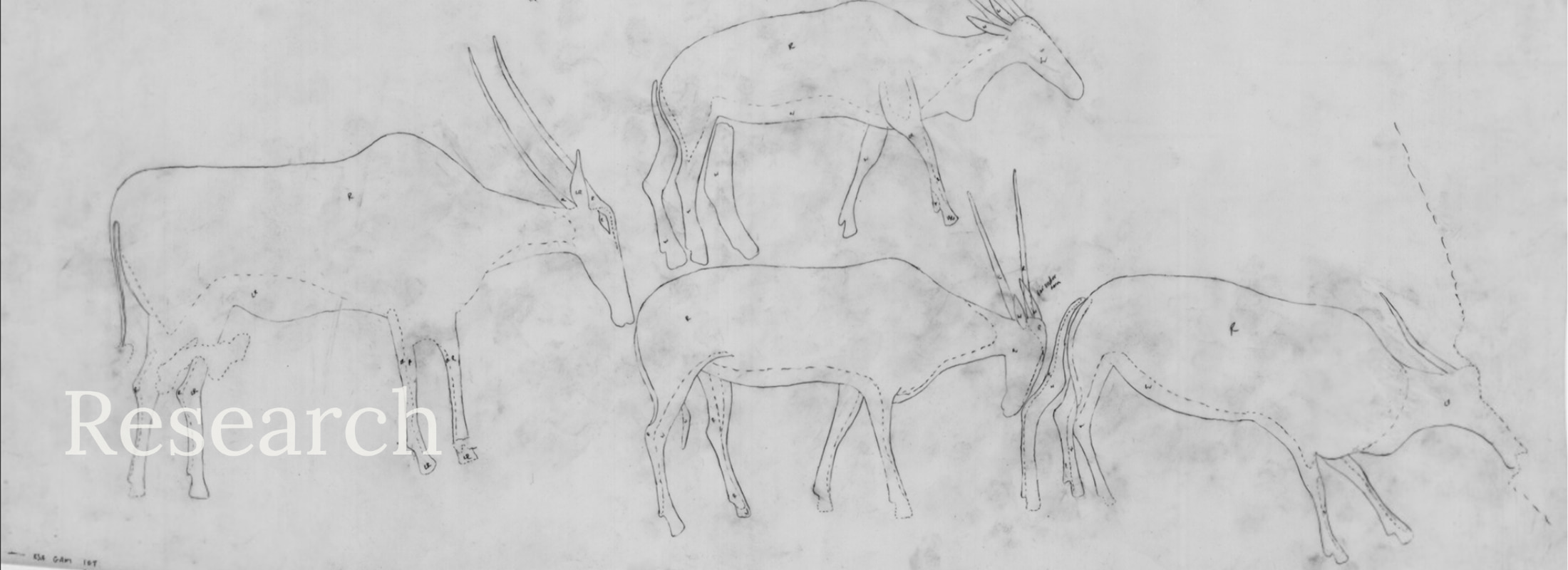

Many experts describe the rock art of this area as the finest in the world, however, it is now known for more than just its beauty. Over 35 years of research at the Institute has contributed to making southern African rock arts some of the best-understood in the world. Using knowledge of indigenous beliefs, researchers have shown that the art played a fundamental part in the religious lives of its painters. The hunter-gatherer art captured things from the San's spirit world behind the rock-face: the other world inhabited by beings of all sorts, to which dancers could spirit-travel, and in which ritual specialists could draw power and bring it back for healing, controlling rain and ‘taming’ wild game animals. The art of herders and African farmers can also be linked to religious experience, particularly the initiation practices of girls and boys. Art of the colonial period was often created by mixed groups comprising all of the above who sought to resist and negotiate their space under Dutch and, later, British rule.

New Research

As the Institute has grown, it has sought to serve multiple regions of the African continent. Currently projects are underway in all South African Provinces as well as in Zimbabwe, Swaziland, Lesotho, Botswana, Mozambique, Zambia, Malawi, Tanzania and Kenya. The SARADA digital archive houses collections from several of these nations.

This new research is rich in its diversity; it includes the rock arts of San and Pygmy hunter-gatherers, Khoe and Nilotic pastoralists, as well as of African farmers such as the Chewa and the Northern Sotho, and the rock art of mixed raiding groups. Underpinning this diverse research is a focus on the complex symbolism of African image-making. In particular, the Institute seeks to understand, through rock art, how people in Africa perceived and responded to social changes during the last ten thousand years and through the colonial process; in this manner the Institute strives to produce a history of the continent that is based on African perceptions rather than just colonial records.