Pleasure in form

- Ufrieda Ho

There's a piece of the artist in every shape that Dr Laurence Chait creates

The beauty of getting older, says Professor Laurence Chait, is reaching a point of giving less of a damn about things that should matter less.

Chait (75) is not a rebel without a cause. Rather, it’s because he’s learnt to honour his own process, to keep his sense of humour and to say no, even to seemingly good things.

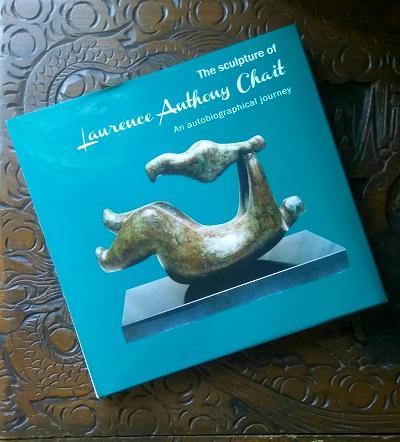

He chats to us as he pages through his recently published coffee table book, The Sculptures of Laurence Anthony Chait. Chait turned down a publisher’s offer to give the book a mainstream and commercial life because he wanted to tell the story in his own way, not necessarily with a publishers’ direction or dictates.

“I wasn’t interested in selling the book to the general public,” says the plastic surgeon of the book dedicated to his other life – that of a sculptor.

It was four years ago, when Chait (MBBCh 1968) and his wife Irene (BA 1972) were packing up their lives to move from one house to another, that the idea for a book emerged.

The younger of their two daughters, Carla (BSc 2003, BSc Hons 2004, BA Hons 2015, MA 2017), was sorting through her father’s things in his crammed studio, where he had worked for 30-odd years. She happened upon a stack of photo albums. Committed to the sticky pages were photographs and newspaper clippings that told the story of an artist’s growth, his development through the decades and the acclaim and accolades he had almost forgotten about.

Carla knew the studio well while she was growing up. Many Saturdays she and her sister, Melissa (BSc 1998, BSc Hons 1999, MSc 2001), would leave their shoes at the studio door and peek into the room to watch their dad at his work bench, taming concrete into shape and form. As an adult she wanted to fill in the gaps and to preserve the stories of her father’s artistic life.

“We agreed to have an ongoing conversation, which I would record, where he talked me through each album and period of production, from the slides of the forms that he made in the very beginning, through the black and white photographs pressed behind thick plastic sleeves, to the sepia-coloured ones, and up to the most recent digital images,” writes Carla in the foreword to the book.

It took four years to complete the pictorial autobiography. Paging through it with Chait in the house that’s now home, it reveals honest reflections and nods to family, friends and colleagues. There’s a strong connection to Wits University and the Medical School and there’s even a chapter dedicated to the foundry that has shaped so many of Chait’s creations over the years.

The book begins with an early memory. Chait says: “I remember making an elephant out of plasticine as a child and my mother commenting that it was so good that I would surely become a plastic surgeon like Jack Penn [MBBCh 1932], who was a well-known doctor at the time.”

Her words seemed to cement Chait’s fate when after school he started his studies to become a doctor and later to specialise in plastic and reconstructive surgery. It was also while he was at medical school that Chait started sculpting. He sort of fell into it, he says.

Chait says he had always been a keen painter and was excited to set up a kind of artists’ salon for the health sciences students at the time.

“It was really a way for those in the department who had an interest in art to show their works and we gave away prizes too. I submitted some paintings and when I didn’t win I realised that I wasn’t that good a painter, so I turned to sculpting,” he says.

Sculpting was shapes and forms and the tactile enjoyment of turning something like concrete into something pleasing to him. Even now Chait is quite blasé about his gift and the techniques he developed. The art critics, though, recognised his talent early on.

Soon after he qualified as a doctor he had his first one-man sculptural exhibition at the Lidchi Gallery in Bree Street in Johannesburg in 1975. The cement sculptures he made for the show garnered acclaim, with adjectives like “rhythmic and faultless” from the newspapers. His artworks also sold well.

He worked on his technique, treating the concrete to create unique patinas, warmth and polish. Most of the work was abstract figures at that stage.

The book progresses from those early days to his exploration of sculpting in different media. When a colleague’s brother returned from a trip to what was then the Western Transvaal with a hunk of “wonderstone”, Chait worked with the inherent shape of the black stone and starting exploring carving.

It was the same when he later started to work in wood, giving expression to the grain and the natural shading in each piece. He also started to work on more realistic pieces, often depicting wildlife. And whatever he turned out the collectors and galleries snapped up.

He admits that he tackled each new medium with a relaxed attitude – more adventure than agonising. Perhaps it was because by the 1980s he had a flourishing career as a plastic surgeon. He received his professorship in 1999.

“I have to say I never agonised about my art. It was always pleasure and fun for me – maybe you’re not supposed to say that as an artist, but that was how it was for me,” he says.

It was only in creating busts of people that he got a little more anxious. He became the commissioned sculptor of some prominent Witsies over the years, including images of Dr AJ Orenstein, Dr Cyril Adler, Esther Adler, Professor Bert Myburgh and Professor Phillip Tobias.

Chait remembers how at the unveiling of the bust of Orenstein someone commented that he hadn’t represented the abnormality in Orenstein’s left ear.

“I suddenly realised that as I’d only ever worked from photographs of him that were taken from the front or from his right, I’d never seen this abnormality,” he says with a laugh.

He also remembers that Tobias had wanted to see Chait’s work in progress and was quite specific about guiding Chait’s interpretations of the famous palaeoanthropologist’s features. Tobias loved the end result.

Chait remembers all these anecdotes with laughter. Because he believes art is deep personal gratification above all, not pleasing critics. He learnt this too from years ago when he gave sculpture classes to his registrars.

“Some works were better than others, but I realised that I didn’t have the right to be critical of someone’s artwork, because they had poured so much of themselves into it,” he says.

It’s a lesson of discipline, effort and courage when you set out to achieve something, but it’s also about relaxing enough to allow the creative process to happen.

“There is a piece of me in everything that I’ve created and I’m happy that they’ve made many people happy,” he says.

Chait is not retired from his practice or his art studio. When he’s not consulting he is working to turn some of his earlier, smaller works into large sculptures. He also continues to accept private commissions. Above all he’s intent on enjoying every bit of it.

His book concludes with a photo of him in his studio with his two granddaughters. They’re making plasticine animals, not for approval from their granddad the artist and professor, but just because they can muck about together and create things that delight them all.