Learning in a post-truth world

- Heather Dugmore

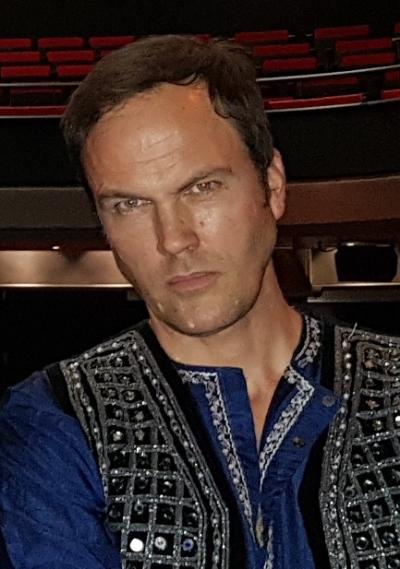

Educators are grappling with the exciting, chaotic, fast-moving era we live in, says Dr Conrad Hughes

Wits alumnus Conrad Hughes (PhD 2008) is the Director of the world’s first international school, La Grande Boissière, in Geneva, Switzerland, where he has lived since 2005.

He frequently returns to South Africa, where his father (Wits Professor Emeritus Geoff Hughes) and brother live. His late mother, Dr Jean Marquard, lectured in the English Department at Wits from the mid-seventies to the mid-eighties before she passed away at a young age.

“It is very important for me to take my wife, Estelle, who is from Cameroon, and our two children, Heloise (13) and Melchior (12), back to my home country,” says Dr Hughes. "I am immensely proud of South Africa; I love this country and the spirit of the people, and both Estelle and I thrive on the music and culture. In addition to being educators (Estelle is a French teacher), we are both musicians, I sing and play guitar and Estelle sings.”

Music and education brought them together in Montpellier in the south of France and they have a sought-after band in Switzerland called Pososhok. “It’s a Russian word, a tribute to a Russian friend, colloquially meaning ‘one for the road’ but literally meaning a walking stick, an extra support in life,” he explains. Their music is not at all Russian; it is a blend of South African folk pop, Cameroonian music with accents of rock, West African influences and Mexican and European influences. “It’s diverse!” says Hughes. “Our drummer is from Senegal, our percussionist from Burkina Faso, our other guitarist is Mexican and our bassist is French.”

Diversity and information literacy

Diversity is the essence of the International School of Geneva, which has learners from over 130 different cultures, and which strives to make the world a better, more peaceful, open-minded place through education.

In February 2018 at the African Education Festival in Ghana, Hughes spoke about thinking and educating for the 21st century, focusing on academic honesty, information literacy, post-truth politics and Big Data.

“We are in an exciting, chaotic, fast-moving period of history, and schools and universities worldwide are grappling with this. It’s an important development as it addresses key aspects of sociology, ideology, politics, education and culture.

“Our school believes in an international curriculum that exposes all learners and students in the world to the diverse historical and contemporary conditions of all humankind. This includes literature that opens new mental gateways and exposes people to different cultures and systems, including Chinese, Indian and African knowledge systems and world religions.”

Access to knowledge is greater than ever before with the internet, he adds, but there is a worrying caveat. “Learners and students are living in a world of Big Data and post-truth politics where we have more information circulating than anyone could have imagined, but what is the source of that information and how do you prevent specific cultures from dominating the internet? How do you prevent confirmation bias? You can google anything and have it confirmed these days – from pyramids on Mars to the American president being a member of the Illuminati.

“People worldwide are creating their own truths and information is being used to wield power more effectively and manipulatively than ever before. This is dangerous as it opens the door to revisionism and conspiracy theories, making it difficult for educators who need to instil the notion that while there is a vast, subjective continuum, there is still truth and falsehood.”

He explains this as follows: As South Africans we know that apartheid happened and while apartheid still exists in various ways, there is no denying it happened: that’s a truth. In Australia, however, there is still a lot of denial about what happened to the Aboriginal people. In Europe, mainstream discourses view the Roma in extraordinarily prejudiced ways. Without accepting the past, how will we reduce our prejudices of the present? Education has a lot to undo and redo in this regard.

How to challenge prejudice

The power of prejudice and how to challenge it in education is addressed in Hughes’ book Understanding Prejudice and Education – The Challenge for Future Generations (Routledge, 2017).

“The way we filter the endless stream of information rushing at us every day is by simplifying it and categorising it – and we do the same with human beings,” he explains. “This leads to prejudice and stereotypes mixed with emotional insecurity and fear.”

He believes that all educators need to teach what prejudice is and how it works. “It is part of a larger idea of metacognition, of knowing about knowing, learning about learning, helping leaners understand the process of learning and meaning-making and that their impulses and assumptions tend to be prejudiced. This is the first step towards reducing prejudice: becoming aware of this blind spot. Furthermore, to become a critical thinker, capable of good judgement, one should be guided by the ground rules of respect and the equal value of human beings.”

The educational benefit of reducing prejudice is that it helps to develop learners and students who are open-minded and eager to expand their perspectives. This builds up a repertoire of thinking skills that advances all-round learning ability, he explains. “At my school we run a lot of workshops on the philosophy and practice of education, not only for the learners but also for parents. We invite parents to co-learn and to give lectures on their area of expertise.

“Education is, after all, a vast enterprise in which we all need to play our part as it certainly does take a village to raise a child.”