Art as a weapon in South Africa’s liberation struggle

- Arianna Lissoni

A retrospective exhibition displays the key works from the life and times of activist and artist Judy Seidman.

Judy Ann Seidman and her artwork embody the feminist maxim that the personal is political, and the political is personal. US-born Seidman is an artist and activist based in South Africa who, for more than four decades, has contributed to defining the iconography of the country’s struggle against apartheid and injustice.

An exhibition at Johannesburg’s Museum Africa, Drawn Lines, follows her life trajectory, and provides a significant retrospective of her work. Her story is inseparable from the movements she has been part of, which in turn shaped her artistic style and praxis.

Seidman’s artworks are revolutionary weapons. She is behind some of South Africa’s most iconic liberation struggle images, each of which has a story to tell that is both personal and political. Many of these stories can be found in her self-published memoir, also titled Drawn Lines.

The posters on the wall

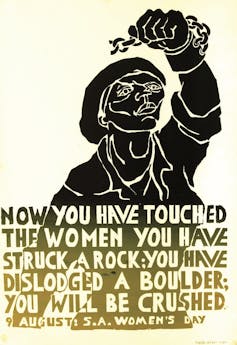

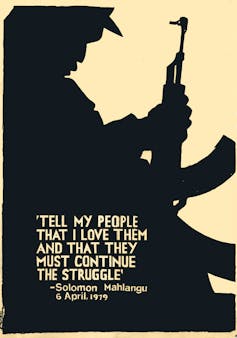

Among the works in the exhibition are the posters for Women’s Day and Solomon Mahlangu – a young man hung by the apartheid regime for his military activism.

Seidman made the Women’s Day drawing in 1981 as part of a brief to position women in the struggle. It was inspired by the women who marched to Pretoria on 9 August 1956 to protest the introduction of passes for women. In the liberation movement, the date was celebrated as a ‘national day’ and officially became a public holiday after the end of apartheid.

The words in the poster were developed by the Medu Art Ensemble collective which was based in Botswana and which Seidman joined in 1980: “Now you have touched the women/ you have struck a rock/ you have dislodged a boulder/ you will be crushed.”

They come from the song ‘Wathint’ abafazi, wathint’ imbokodo’ (‘When you strike the women, you have struck a rock’), sung by the marching women in 1956. The original drawing had the woman holding up an AK47 rifle, but the collective felt that in the light of increasing raids by the apartheid regime, the picture should not show close alignment with the armed struggle. A broken chain came to replace the gun.

The Solomon Mahlangu poster was designed for the 1982 anniversary of the 19-year-old uMkhonto weSizwe operative’s execution at the hands of the apartheid regime in 1979.

A few hundred copies were silkscreened by Medu members, several of whom were also part of uMkhonto weSizwe structures, with the help of soldiers passing through Botswana. The works were then smuggled into South Africa and illegally displayed by members of the Johannesburg Silkscreen Training Project. They were torn down by the police the next day, but this poster remains one of Seidman’s best known.

Another poster mourns the death of 12 comrades in the Gaborone raid of 1985. Among the dead was Thami Mnyele, a fellow Medu member and an important influence on Seidman’s work and understanding of the art of liberation.

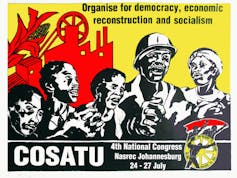

Seidman moved to South Africa in 1990 after the unbanning of the liberation organisations. She was commissioned to draw the poster for the 1991 congress of the Congress of South African Trade Unions.

She also designed a poster for the Convention for a Democratic South Africa negotiations: a rising sun symbolising a new dawn for the people of the country.

In the early 1990s Seidman and her partner Serge Phetla, an uMkhonto weSizwe combatant, were diagnosed HIV positive. No antiretroviral treatment was available at the time, and their status was not made public for political reasons.

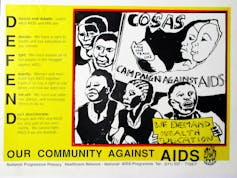

She increasingly did artworks for Aids activism – among them a 1991 poster for a Congress of South African 足球竞彩app排名s campaign against Aids.

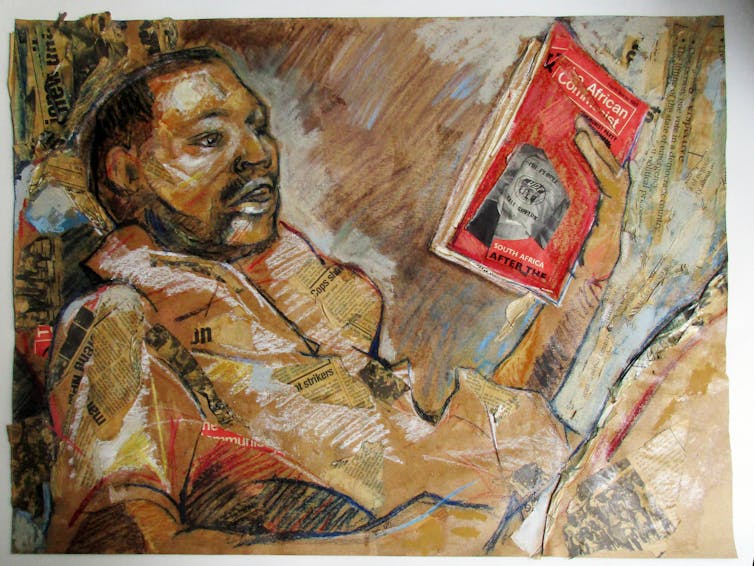

With the advent of democracy, Seidman came out publicly about living with HIV. Serge died just before the first democratic elections in 1994. An intimate portrait of him reading a copy of the African Communist is part of the exhibition.

A life fully lived

The exhibition provides a chronological unfolding of Seidman’s life. It starts with her time in Lusaka, Zambia, where she arrived for a visit in 1973 after graduating with a Masters in Fine Arts in the US.

Her parents, the Africanist economist Anne Willcox Seidman and Bob Seidman were working at the University of Zambia, while her sister Neva was a secretary in the office of the ANC’s external headquarters. Seidman’s first encounter with the ANC was in the context of an exhibition, for which Neva asked her ‘friends’ in the ANC office to help transport her sister’s artworks.

Among them was a young man called John Dube (JD) whose real name was Boy Mvemve. A few weeks later, he was killed when he opened a letter bomb sent by the apartheid regime. Seidman silkscreened a poster for JD’s funeral. It was to be the first in a long series of drawings she did for the ANC and allied organisations.

In Lusaka, Seidman fell in love with and married historian Neil Parsons and in 1975 they moved to Swaziland where he took up a lecturing post. It’s also where their first daughter was born.

In Swaziland, Seidman worked with the sculptor and writer Pitika Ntuli, whose vision of art and revolution had a great impact on her. Both had studied in Kwame Nkrumah’s Ghana in the early 1960s and had been influenced by Pan-African ideals.

In 1980 Seidman moved to Botswana with her family. She carried with her a letter of introduction from writer and activist Barry Feinberg addressed to Thami Mnyele and Mongane Wally Serote, then leading figures in Medu.

Medu is a SePedi word meaning ‘roots’ and for Seidman the ensemble’s idea of art as rooted in experience, its explicit commitment to work as a collective and its alignment with South Africa’s black majority were “like coming home”.

This was a time of political and cultural ferment in the liberation movement. The Gaborone Culture and Resistance Festival in 1982 marked a significant moment of discussion about the art of liberation. These ideas, Seidman argues, have largely been lost post-1994 as the ANC failed to support the revolutionary culture of the liberation struggle.

Seidman remained in Botswana, by now working within uMkhonto weSizwe structures. This led to the breakdown of her marriage, and her two daughters moved to the UK with their father after their house in Gaborone was petrol bombed in 1986.

At the turn of the century she worked with the Khulumani support group to support victims of political violence. She also got involved with the One in Nine campaign which campaigns against gender-based violence and whose work forms ‘an exhibition within the exhibition’ with four panels dedicated to it.

The last section, which Seidman dubs the “cultural wall”, showcases recent work associated with music and recent struggles such as #FeesMustFall.

The exhibition underscores the message that, in her life and in her work, Seidman drew a line and has never been afraid of taking sides in ongoing struggles for liberation.

Drawn Lines is on at Museum Africa in Newtown, Johannesburg, until the end of January 2020, with further extensions expected. Admission is free.![]()

Arianna Lissoni, Researcher at History Workshop, University of the Witwatersrand. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.