Using the court to secure water rights

- Zeenat Sujee

Access to sufficient water is a human right but failures of government often compel people to access this through law.

Water is a basic necessity yet thousands of South Africans are living without water. There may be many different reasons for this water scarcity including climate change and droughts, but often it is due to failures of government.

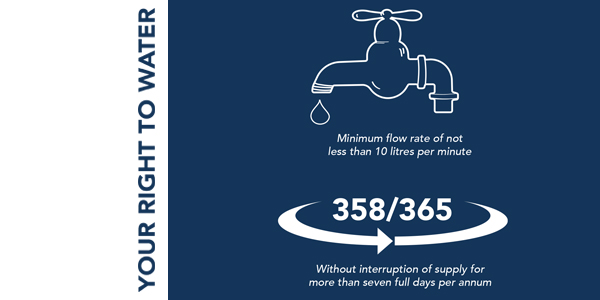

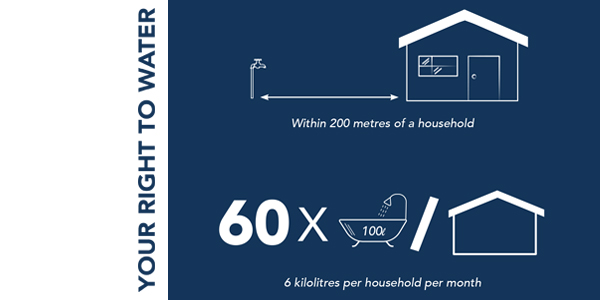

Despite the scarcity of water, Section 27 of the Constitution of South Africa gives everyone the right to access sufficient water. The Water Services Act prescribes 25 litres per person per day as a minimum standard of basic water supply services (or 6 kilolitres per household per month), at a minimum flow rate of not less than 10 litres per minute, within 200 meters of a household and without interruption of supply for more than seven full days per annum.

The Constitutional Court emphasised the state’s obligations to fulfill the right to access water. In its judgment on a case brought by Lindiwe Mazibuko against the City of Johannesburg, the Court stated: “At the time the Constitution was adopted, millions of South Africans did not have access to the basic necessities of life, including water. The purpose of the constitutional entrenchment of social and economic rights was thus to ensure that the state continues to take reasonable legislative and other measures progressively to achieve the realisation of the rights to the basic necessities of life.”

How much is enough?

The case of Mazibuko concerned a community residing in Phiri, Soweto. The community challenged the free basic water policy. In 2009, the Constitutional Court dismissed the application, ruling that the requested 50 litres per person per day was not reasonable. The ruling was widely criticised for the Court failing to consider the needs of the community. This case did not deal directly with access to water, but rather with the quantity of water.

Governance acid test

Access to water was the focus in the case of the Federation for Sustainable Development against the Minister of Water and Sanitation. The community residing in Siobela, Caropark, Carolina in Mpumalanga had no access to potable water due to acid mine drainage. The municipality installed JoJo tanks to supply the community with drinking water, but failed to refill the tanks. The communities were left with no option but to walk long distances to access potable water.

In this case, the Court ruled that the municipality must act urgently to remedy the violation and ordered that, on an interim basis, the municipality provide potable water to the community and, in the longer term, report on their plans to provide water supply.

Trickle-down effect of poor governance

The failure of municipalities to provide water, especially in rural areas, has dire consequences. One such case involved five community villages situated at least 30km outside of Marble Hall, Limpopo. The communities stopped receiving water after the municipality shut down a water treatment plant in 2009. The termination of water was unlawful and the community was forced to collect water from a crocodile-infested river, where a child was attacked. Women were violated while collecting water. School children attended school thirsty and with unwashed clothing. Menstruating girls were absent from school.

In 2015, these communities, represented by the Centre for Applied Legal Studies (CALS) at Wits, approached the High Court for assistance. Through a settlement negotiation, the Court ordered that water be supplied through JoJo tanks as an interim measure. The municipality failed to comply with the court order. Consequently, CALS initiated contempt proceedings.

The second aspect of the application was to deal with the long-term water supply. In August 2017, Judge Hans Fabricius requested that the parties discuss a workable solution. His view was that the community be treated with respect and that the municipality fulfill its constitutional obligations. Again, the parties negotiated and agreed that the municipality would install more JoJo tanks and deliver water every day. It was further agreed that the municipality would supply water through reticulation twice a week. Judge Fabricius agreed to manage the case.

Again the municipality failed to comply. The community approached the High Court for contempt of court and Judge Fabricius requested that the Minister of Water and Sanitation, Nomvula Mokonyane, intervene. To date, CALS has not received any response from the Minister.

The municipality failed to meet its obligations to supply water in terms of law and it is disappointing that it reacted only once litigation was instituted. Litigation, although not always favoured, is always the last tool – and the only option – for redress when communities have no access to water supply. It is unfortunate that communities must endure a protracted process to secure this basic constitutional right.

Zeenat Sujee is an Attorney in the Basic Services Programme in the Centre for Applied Legal Studies (CALS) at Wits. She has litigated in the High Courts and Constitutional Court of South Africa, representing communities in cases concerning access to housing, water, sanitation and electricity. She holds an LLB and postgraduate diploma in Human Rights. She researches the intersection of socioeconomic rights and gender.