mARTdiba

- Lem Chetty

In Nelson Mandela’s personal office in Houghton, there is a stately wooden desk covered in brightly coloured cattle figurines.

The artworks form part of a vast collection of gifts to Madiba, the beloved icon whose image artists preserved in wood, copper, bronze, clay, ink and on canvas. The Nelson Mandela Foundation’s Verne Harris chuckles when he recalls the cattle.

“Madiba avoided saying what his favourite things were, because it excluded people, but if he liked something, it would go to his office or to the house. The porcelain herd he loved because it reminded him of his actual cattle in the Eastern Cape,” says Harris.

In a basement of the Foundation’s offices, Harris opens a vault that houses “Madiba Art” that has been catalogued and curated over the years. “Value is subjective. Some of it is fantastic, some quite grotesque,” Harris says, recalling a bust of Madiba in papier-m?ché, painted gold, that was created by a prisoner in Johannesburg. The Foundation went to visit the prisoner to thank him for the effort, says Harris.

The vault is filled with macabre masks, statuettes, and endless rows of paintings, including one from actor Robert De Niro, whose father was a renowned artist. A gift from Michelle Obama, former first lady of the USA, is a bizarre three-armed bronze of Dr Martin Luther King, but most of the art depicts Mandela himself – in every medium, form and size imaginable.

Another art haul is expected for Mandela’s centenary – this is apart from street art around the world that depicts Mandela in mosaic, graffiti and abstract pieces as far as Venice Beach, Los Angeles; Paris, France; and Bristol, England.

“I think artists depicting Madiba make the mistake of not interpreting him. Just trying to depict him was not easy at all. But it also loses his soul,” says Harris. “Zapiro [cartoonist Jonathan Shapiro] does a great job of depicting his personality. The cartoons are my personal favourite,” he says, revealing an ink drawing by a US cartoonist of former first lady, Gra?a Machel and Madiba, beaming from their disproportionate caricatured faces.

Whether as street art for a hair salon, murals, or towering statues around the world, Mandela was humble about art dedicated to him, says Harris. The nine metre bronze statue at the Union Buildings in Pretoria – as famous for its grandeur as for the fact that the sculptor hid a tiny rabbit in Mandela’s ear – had people up in arms because they felt it disrespected the icon. Harris says the Foundation did not take a position on it, because Mandela was shy about grand gestures in general.

“When he got back from London from unveiling a statue in Parliament Square he said, ‘Please, don’t make any more statues of me.’ I think he was awkward about the iconographic nature of it,” says Harris.

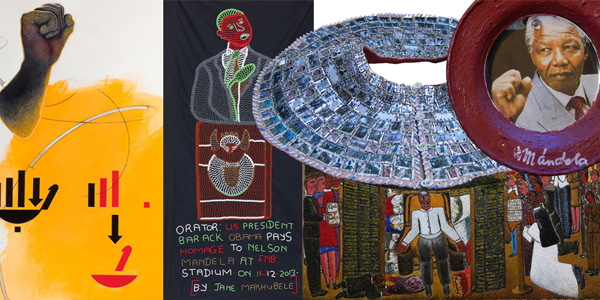

There is a cache of valuable Mandela art, some priceless, such as the famed South African artist, Marlene Dumas’ painting held at the Apartheid Museum. For curator and Wits alumna, Natalie Knight, who produced one of the biggest exhibitions of professional art dedicated to Mandela at the Origins Centre at Wits in 2012, it is in the eclectic and unusual that you see the adoration of Mandela. Her favourites include the works by Joachim Schonfeldt, circular paintings depicting Mandela’s life in the townships, Jane Makhubele’s Madiba shirts made from gold-plated safety pins, and Collen Maswanganyi’s sculpture, Fruits of the Long Walk to Freedom.

“These works I have kept in my personal collection – except for the sculpture by Collen which was sold after the show. A work that I find particularly poignant and that I am exhibiting in the 2018 show is a work by Velaphi Mzimba. He created his work on an old door that he found in his garage. He chose the moment that Mandela was released after 27 years in prison, and he based it on an extract from the book, The Long Walk to Freedom: ‘As I walked out of the door towards the gate that would lead to my freedom, I knew that if I didn’t leave my bitterness and hatred behind, I’d still be in prison’,” said Knight. One of the highlights of the exhibition was a lithograph, titled Tennis Court, by Mandela himself.

Knight recalls another show, which she curated in London at the South African Embassy in 2013, a few months before Mandela’s death. “The theme was, We love Mandela. All the artists, including Zapiro, known for his vitriolic depictions, showed their love and reverence for Mandela – except for artist Alfred Thoba, who was critical of Mandela and the ZCC [Zion Christian Church],” she said.

There are several exhibitions scheduled for the centenary. Music, art and theatre will converge to remember and honour Mandela. Whether priceless kitsch or invaluable artefact, it's all testament to the ideals that Mandela stood for, and for which South Africa and the world yearn.

As Knight says: “Art is a permanent record of the time. History and words can interpret and alter facts but a painting captures the moment and it is frozen in time. Mandela’s invaluable contribution should never be underestimated. His name and legacy should be acknowledged and revered.”

- Lem Chetty is a freelance journalist.

- This article first appeared in Curiosity, a research magazine produced by Wits Communications and the Research Office.

- Read more in the fifth issue, themed: #Mandela100 where Wits students, academics, researchers, activists and leaders reflect on Nelson Mandela’s legacy and explore his impact over a lifetime.