Killing cancer with cryoablation

- Deborah Minors

Freeze, fry, microwave, or obliterated – treating early cancer which can progress to advanced life-threatening cancer with cryoablation.

When 75-year-old Kennethy ‘Kenny’ Siphayi went for a check-up after surgery to treat an enlarged prostate, he didn’t expect to have a renal cell carcinoma uncovered in his left kidney. Carcinoma is a cancer arising in the?tissue of the skin or any of the internal organs.

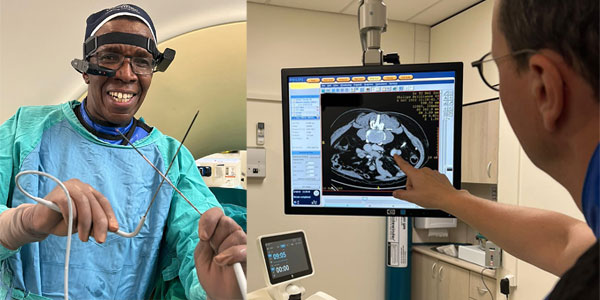

Kenny’s urologist referred him to Dr Charles Sanyika, Head of Interventional Radiology at the Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre (WDGMC). Interventional radiologists?diagnose and treat a range of conditions by inserting instruments – catheters, wires, needles, probes – from outside the body using imaging technology such as X-rays, CT scans and ultrasounds.

Sanyika was preparing to pilot a pioneering technology called cryoablation – a first in southern Africa for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma.

“Cryoablation is a treatment that had not been available in the country previously for patients with early renal cell carcinoma, the most common type of kidney cancer,” explains Sanyika. “It’s a minimally invasive intervention where we insert a needle [probe] into the cancer mass and create very low temperatures, between minus 20 and minus 40 degrees Celsius, which result in cell death.”

Cold-shouldering cancer

Ablation is the removal or destruction of a body part or tissue by freezing or by radiofrequency, heat, hormones, drugs, or surgery. In Kenny’s case of cryoablation – from the Greek ‘cryo’ meaning cold – extremely cold temperatures are achieved by use of flow dynamics of the argon gas (a non-corrosive gas) to freeze and kill malignant cells in his kidney.

Kenny recalls his urologist’s explanation of the procedure, about which Kenny was understandably originally quite anxious: “I must be honest with you, I was very, very worried, because from the experience of the first operation [prostrate] … they put in a needle…it was a little bit sore, so when he told me of this kidney operation, I was a little bit worried,” said the Soweto resident and father of four.

Despite Kenny’s initial reservations, it transpired that he was an ideal candidate. “Tumour ablation, more specifically percutaneous cryoablation, has emerged as an alternative to surgery in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma and particularly for early-stage renal cell cancer tumours, that is, localised and smaller than 4cm,” says Eleanor Joubert, a Senior Field Clinical Specialist at Boston Scientific, a biotech firm that manufactures medical devices used in interventional medical specialties, including in Kenny’s procedure.

Sanyika elaborates: “Cryoablation enables treating early kidney cancer without the patient going under the knife. We used the ICEfx Cryoablation System, a gas cylinder, and a needle – this does the freezing. With surgery, there is removal of part of or the whole kidney, but cryoablation is minimally invasive and zaps just the tumour and a bit of the kidney around it.”

Freeze, fry, microwave

Although Kenny’s was among the first cases of cryoablation locally to treat renal cell carcinoma, the procedure is being used internationally to successfully treat several benign or malignant tumours in the lung, prostate, breast, and the musculoskeletal system, as well as in the management of pain. The safety, efficacy and the ability to visualise the ice formation on radiographic imaging enables the use of cryoablation in many different treatment sites within the body.

Dr John Cantrell, an interventional radiologist at the WDGMC who participated in Kenny’s procedure, explains that cryoablation is just one way to eliminate a tumour.

“There are various ways to kill the tumour without cutting it out – you can inject chemotherapy into it, you can inject alcohol into it, you can inject radioactive beads into it.”

The nature of the tumour dictates how oncologists will attack it and radiation oncologists can shape the radiation field to correspond to the shape of the tumour. Cantrell says that to freeze or heat a tumour, doctors need some overlap between the edge of the tumour and the healthy tissue surrounding it.

“The advantage of cryoablation is that it preserves the collagen architecture of the adjacent organs, so you can still get your margin and kill the tumour cells, but you’re not going to make a big hole in the chest wall, for example, as you would for the heating.”

Today Kenny is alive and thriving. He reports that, aside from a bit of post-operative blood where the probes were inserted, his recovery had been comfortable, the procedure mostly painless, and he was discharged the same day.

“In the past, when you have cancer, it was one way: You would think that no, I’m going to die. But today it’s different. The country has improved a lot, doctors have improved a lot – that [they] can kill that tumour that’s now cancerous in your body and you still manage to live! I’d advise whoever has a problem of this kind should not be unhappy. They mustn’t worry that much because there’s a solution for it.”

- Deborah Minors is Senior Communications Officer for Wits University.

- This article first appeared in?Curiosity, a research magazine produced by?Wits Communications?and the Office of the Deputy Vice-Chancellor:?Research and Innovation.

- Read more in the 15th issue, themed: #Energy. We explore energy research into finding solutions for SA's energy crisis, illuminate energy needs of people with disabilities, address the energy and digital divide in an unequal society, and investigate the origins of fire control.